Genetic Testing Uncovers Unknown Autoinflammatory Disorder

Suzanne Gold

Living with unexplained fevers, feeding problems, digestive issues, an enlarged spleen, occasional rash and other seemingly unrelated symptoms dominated the first seven years of Claire Gvozdanovic’s life. Though she saw a variety of specialists, they could never quite pinpoint the cause of her puzzling medical issues. Was it an infection? A blood disorder? Eventually, her rheumatologist at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) determined that the condition was actually an autoinflammatory disorder. However, her particular case did not fit into the pattern of any previously-identified types. Her clinical team managed her symptoms with steroids and other powerful medications, but she continued to struggle with flare-ups.

Finally, in April 2013, Claire underwent a series of tests including whole exome sequencing at the autoinflammatory disease clinic at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD. Seven months later, the NIH team was able to identify a genetic mutation in Claire that had not previously been seen. This information enabled her doctors at SickKids to offer her a more targeted treatment that has kept her symptoms at bay.

The previously-unknown autoinflammatory disorder and its treatment are described in a new study published in the Sept. 14 advance online edition of Nature Genetics. The discovery is reported by researchers at SickKids and the NIH.

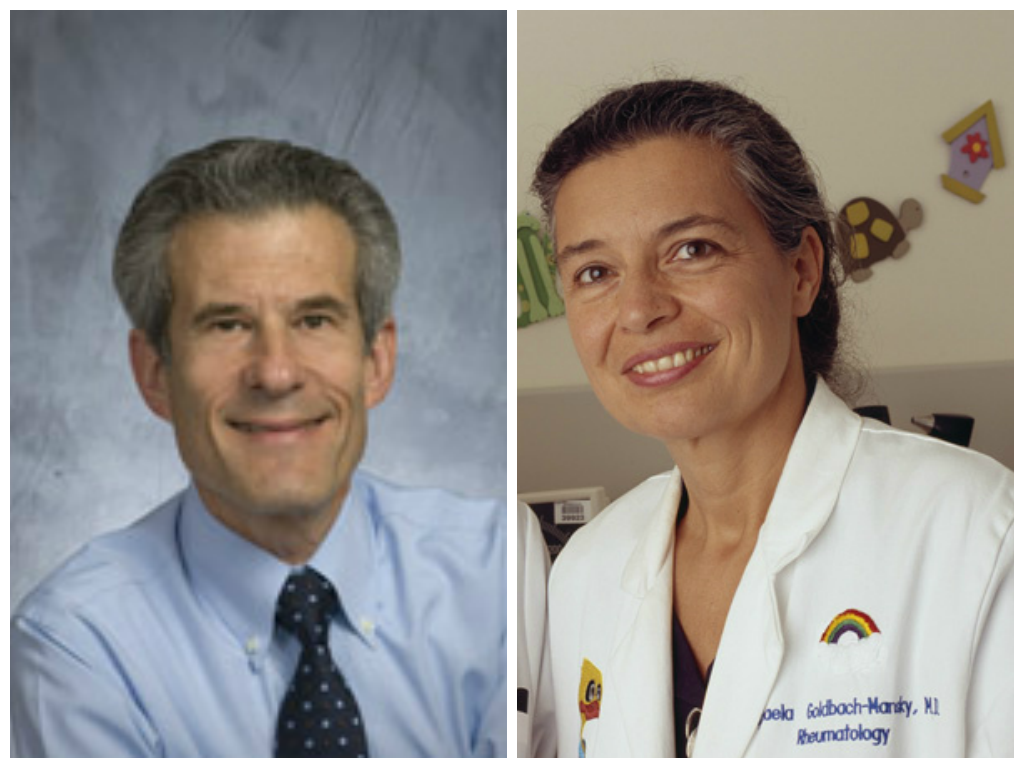

“As clinicians, it’s crucial to be able to access the tools to figure out what is unique about the patient; in this case, the collaboration with the NIH led to successful targeted therapy for Claire,” says Dr. Ronald Laxer, Professor in the Departments of Paediatrics and Medicine at the University of Toronto. he is Claire’s current rheumatologist, head of the Fever Clinic at SickKids and a senior author of the paper. “The study tells us there are other new inflammation pathways to be explored, which lead to different disease manifestations. Now what we can do is work backwards. In some cases where symptoms have been recurrent but not explained, maybe we ought to be looking for the same mutation and then trying to determine which inflammation pathways may be involved.”

Autoinflammatory disorders are a class of immune disorders that occur when the immune system – normally functioning as the protector of the body against infection – is activated and leads to spontaneous episodes of inflammation that include fever or rashes, among other symptoms. Prolonged and untreated inflammation could cause severe problems, including eventual organ damage.

The fevers that were part of Claire’s illness led to a complication called macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a serious and potentially fatal disorder. In MAS, immune cells called macrophages are activated uncontrollably and produce inflammatory proteins, leading to a marked systemic inflammation response.

Prior to the genetic testing, Claire’s combination of powerful medications resulted in some symptom control but did not prevent unpredictable flare-ups, affecting her growth, appetite, school performance and overall health. Being on corticosteroids caused side-effects including moodiness and growth delay, so her clinical team managed her dosage carefully and tried to lower it when possible. Usually the symptoms would return within a few days of reducing the dose to a certain level.

Following the tests, the team, under the direction of Dr. Raphaela Goldbach-Mansky, determined that Claire’s still-unnamed condition was caused by a mutation that resulted in hyperactivity of a protein called NLRC4. NLRC4 is an immune sensor that belongs to a family of proteins called NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and when activated, it forms a complex called NLRC4 inflammasome that releases the inflammatory proteins interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and interleukin 18 (IL-18). In Claire’s case, the mutation caused the NLRC4 inflammasome to be hyperactive and this manifested as early-onset recurrent fevers with MAS.

With this knowledge, Claire’s clinical team prescribed a targeted treatment proven to be an effective IL-1 inhibitor in autoinflammatory diseases linked with a similar protein, NLRP3. The drug, an IL-1 blocker called anakinra, has substantially reduced all of her symptoms and the frequency of her flare-ups. As a result, Claire was slowly weaned off the other drugs, with no recurrence of her symptoms.

“She was on medications that were toxic and not totally controlling her disease,” says Laxer, who is also Project Investigator at SickKids. “She would continue to get flares, despite the strong medications we were using. We were pretty much using a cannon instead of targeted therapy, which we are now able to give her.”

Claire’s mother, Karen Alguire, says she hopes her family’s experience and the identification of Claire’s disorder will help clinicians identify other patients’ unknown autoinflammatory diseases. “Not knowing what Claire’s condition was had been so overwhelming for our family. It was a trying time for us,” she said. “Claire’s doctors never stopped pushing for answers. There’s so much potential that this discovery could help other families who are searching for a diagnosis. Even if it’s not the same condition, maybe it’ll spark a doctor’s memory and encourage them to keep searching for an explanation.”

The research was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAMS and the NIH, the NIH Clinical Center, and the Arthritis National Research Foundation.

News