Virtual Rehab is Bridging Pandemic Gaps in Care and Research

Imagine this — you’ve experienced a stroke and need physical and cognitive therapy, but hospitals and clinics have suspended these vital rehabilitation services due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Enter Mark Bayley, a professor with the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine whose work focuses on brain injury, stroke and multiple sclerosis.

“After COVID-19 hit, people weren’t able to get the usual outpatient rehab to optimize their recovery and health,” says Bayley, a professor in the division of physical medicine and rehabilitation in the Department of Medicine.

In March, Bayley and his team ordered 30 webcams and developed materials for online care delivery. By April, they were seeing patients virtually in their homes.

“The pandemic changed everything,” says Bayley, who is also program medical director and physiatrist in chief at Toronto Rehabilitation Institute (Toronto Rehab), University Health Network. “It made us rethink how we’re doing things and pushed us to reconfigure our services in a matter of weeks, not years.”

Bayley and his group are one of several across U of T that have turned clinical rehabilitation virtual in the wake of COVID-19, reshaping care and research programs for neurological conditions but also speech and language disorders, and respiratory and other illnesses.

“The pandemic has instigated massive changes right across rehab fields, some of which will likely be permanent,” Bayley says.

Bayley began doing virtual consultations via telehealth over a decade ago, but patients still had to travel to a health centre or hospital for an appointment. With the arrival of the coronavirus, the Ontario Telehealth Network rolled out a new platform called OTN Connect, enabling Bayley and his team to go digital with more patients.

Satisfaction among patients has been high, Bayley says.

Online treatment means patients and their caregivers spend much less time accessing care, avoiding barriers such as transportation to and from appointments, and parking.

The team members — which include Professors Paul Oh (Department of Medicine), Sarah Munce, Liz Inness (RSI), Mckyla McIntyre and Meiqi Guo (division of physical medicine and rehabilitation) — were also interested in studying the process of implementing these changes so quickly.

“When we made the switch to online care delivery, my colleagues and I worried patients might experience technical difficulties,” says Bayley.

Bayley and his team surveyed about 500 patients. In the spring, about 30 per cent said they struggled with the technology. But a follow-up survey in the fall indicated more people were growing used to online appointments, and less than 10 per cent indicated that technology was a barrier.

There are some challenges.

“The tradeoff we’ve noticed is that the rehabilitation service providers have to make some extra effort,” says Bayley. “We’ve also noticed virtual care fatigue among therapists who have found the move online required more preparation, at least for the first few sessions.”

As with most treatments and therapies, online rehabilitation needs to be tailored to the needs of the person receiving it, says Bayley.

Online care also introduces new complexities and questions, Bayley says. Do people have enough space in their homes to safely do their exercises? Do they need equipment? Is there a caregiver there to help them in case they’re doing something challenging and fall over?

To address these and other considerations, Bayley and his colleagues have developed a telerehabilitation toolkit to help people working in the field, based in part on their survey findings.

Bayley says his team is also concerned about the impact of virtual care on those with housing issues, or people who are homeless, and they are working to address those concerns. “Some people may not be able to afford to buy the equipment they need to take part in virtual care,” he says. “We don’t want to create a model that disadvantages or excludes some people.”

Elizabeth Rochon and her team also shifted their approach to care and research. Rochon is a professor of speech language pathology, who has worked with colleagues in Alberta, Germany and Austria to develop an app to help people with aphasia who are having difficulty with word-finding.

Aphasia is a language disorder that makes it hard to produce and process speech. It affects about one-third of people who survive a stroke.

Rochon’s team intended to enroll participants in their study of the app in the spring, then meet in person to set them up. But after the pandemic hit, the researchers shifted their plan and spent the summer developing, modifying and testing tools for use online.

“We work with people who have difficulty communicating and might not be able to express themselves,” says Rochon, who is also a member of the RSI and Associate Director, Scientific at KITE Research Institute, Toronto Rehab. “They might also have motor problems as a result of their stroke and motor abilities are usually necessary for computer use, so we needed to take these considerations into account.”

Working from the isolation of their own homes, Rochon’s group developed ‘cheat sheets’ with a combination of symbols and words that might help someone use the app on a tablet. They also created manuals with visuals and text to help people navigate the video conferencing platforms.

“One upside is that we may be able to include people who live beyond the Greater Toronto Area in our study, whereas originally we conceived it as an in-person project,” says Rochon.

Although a few studies had shown success with remotely delivered therapy, Rochon says there hadn’t been much of a push toward tele-rehab for speech-language pathology services.

“There’s a need for it, but we don’t always know if the results are going to be the same as they would have been in face-to-face settings,” says Rochon. “Like with other data and ongoing studies on COVID, new evidence will emerge.”

Better data will inform the uptake and evolution of virtual services in the future, says another researcher.

Roger Goldstein, a professor of respirology and physical therapy and a member of the RSI, has been seeing patients from other parts of Ontario virtually for about five years.

He specializes in pulmonary rehab for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which causes breathing difficulty.

“Our objective is to teach people how to improve their exercise capacity and quality of life as well as how to reintegrate to the community in times of duress. Most importantly we ensure that they continue progressing through their program,” says Goldstein. “Many patients have expressed how crucial the continuity of care has been throughout the course of the pandemic, amidst their concerns about safety.”

Goldstein is also director of respiratory services at West Park Healthcare Centre, where patients began remote rehabilitation programs in the spring.

The half-hour, semi-weekly classes help people work on flexibility and strength. The centre also designed modules available to help patients better understand and manage their respiratory conditions.

Most patients moved to an online system via Ontario Telemedicine or Zoom in April.

The remaining group — about 40 per cent — said they either weren’t technically proficient or weren’t interested in using a device like a tablet or computer. That cohort used a telephone system to take part in the programs.

Goldstein had previously published work on telemedicine in COPD, but he says the pandemic catapulted work in this area forward out of necessity.

Some of his current research involves defining best outcome measures when health care providers can’t see their patients in person. The project is a collaboration with sites in Montreal and Edmonton and involves creation of an upgraded rehabilitation program, to serve as a Canadian standard.

“Everything we do, we try to answer questions on how best to move the field forward. There are lots of questions now on the timing, the content and the way of delivering rehabilitation,” says Goldstein.

Goldstein, Rochon and Bayley all agree there will always be a need for in-person rehabilitation. But, they say, as pandemic-related concerns over face-to-face gatherings subside, some elements of remote care will remain as the new normal.

“I’m excited — I truly believe that with the latest technology, it will revolutionize care,” says Bayley.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Erin Howe

UofTMed Alum: On the Holocaust's Lasting Lessons

My family has always lived in the shadow of the Holocaust.

My paternal grandmother’s parents and most of her siblings were murdered by the Nazis in the death camps. My mother’s mother also lost both of her parents and several of her siblings in the Holocaust — including her three-year old brother, whom I’m named after.

I am forever in awe and forever grateful to them for living through hell on earth and rebuilding their lives on the other side, raising happy families and establishing supportive communities. But they and their children and grandchildren could never fully escape the traumatic legacy of the Holocaust.

When I was 16, I travelled to Poland to witness the death camps for myself. Confronted by horror after horror, I could hear my peers all around me repeating the same phrase: “How inhuman!”

But the Holocaust wasn’t inhuman. It wasn’t a natural disaster. This, the largest mass killing in history per the UN Convention on Genocide, was the purposeful, planned, carefully executed work of people. Among the most instrumental in justifying, planning, and carrying out these murders were well-meaning doctors.

As a Jewish person and grandchild of survivors, the Holocaust places me in the role of victim, reminding me that I am always vulnerable to the pernicious destruction of Anti-Semitism; but as a doctor, I must grapple with my own profession’s complicity and participation in this horrific atrocity. Instead of dismissing them as simply “bad doctors” and “evil people”, I believe that by confronting physician atrocities head-on, by trying to understand how those committed to helping people could justify hurting people so badly, by acknowledging the shameful parts of our profession’s history, we can learn lessons that help us reflect on the ways we might be inadvertently dehumanizing others.

More than 11 million people were systematically murdered during the Holocaust: six million Jews, 250,000 people with disabilities, 200,000 Roma, thousands of Jehovah’s Witnesses, gay men, Black people, and political opponents, as well as millions more Eastern European civilian non-combatants. And at every step along the way, doctors were there, helping to make it possible.

In 2019, Dr. Richard Horton published an article in The Lancet entitled “Medicine and the Holocaust — It’s Time to Teach” in which he extolled medical schools to integrate Holocaust education into their curricula.

“Teaching medical students about the Holocaust would instil lessons about the equal worth of human beings, the limits of human experimentation, the importance of ethical regulation of research and practice, and the balance between notions of public health and the duty of health professionals to the welfare of individuals,” Horton wrote.

It was a call to action that U of T’s Vice Dean of Medical Education Patricia Houston (MD ’78, PGME ’83, M.Ed. ’00) took up passionately, tapping Ethics and Professionalism Curriculum Lead Dr. Erika Abner (MEd ’98, PhD ‘06) to pursue the development of a learning module in the MD program. Dr. Abner then recruited me, along with Dr. Ayelet Kuper (MD ’01, PGME ‘06, PGME ‘07, MEd ’07), Shayna Kulman-Lipsey, and two student representatives, Jordynn Klein and Jane Zhu, to help guide the creation of a new lecture focused on Holocaust Education.

And so, a few weeks ago, I found myself preparing to speak to the class of second-year MD students on Physicians, Human Rights, and Civil Liberties: Lessons from the Holocaust.

The lessons from the Holocaust are not broadly taught in medical schools, despite being eminently relevant to 21st century medicine. In fact, many of the central ideas that make up modern medical ethics, social justice and the psychology of trauma emerged from the literature and the legacy of the Holocaust.

More than anything, I wanted the students participating in the lecture to recognize that the horrors of the Holocaust are not ancient history, and they aren’t just a sad story. They are exceptionally relevant and meaningful to our conduct as human beings and as physicians today.

In preparing for the talk, I learned that more than half of all German physicians joined the Nazi party early and voluntarily. They supported and led mass sterilizations of hundreds of thousands of people with hereditary diseases. Later, they systematically euthanized children with physical disabilities and people living with mental illness.

Doctors were also key figures in the Holocaust’s death camps — selecting which prisoners would be sent to be murdered, overseeing the gas chambers, and performing cruel medical experiments on non-consenting subjects.

Shockingly, these doctors often saw no contradiction between their actions and their Hippocratic Oaths. They justified them through a twisted interpretation of “the common good.” Jews and other “undesirables” had been so villainized and dehumanized in society, that in the minds of these doctors, their murderous removal from society was akin to the removal of a gangrenous appendix from the body. This teaches us that it isn’t enough to follow our own definition of “do no harm”— we have to constantly reflect on our beliefs and actions, continually questioning our assumptions, biases, power, and privilege.

What does it mean to apply the lessons of the Holocaust to the practice of medicine? It’s more than simply promising not to commit genocidal acts. Dehumanizing discourse is a significant problem in Canadian hospitals, as certain groups of people are cast as less valuable than others or at fault for their misfortune, including the homeless, Black and Indigenous individuals, those with addictions, and those who don’t speak English.

We must cultivate our moral courage and denounce dehumanizing discourse on a large scale and in our daily practice. We must use our privilege as physicians to stand up against unethical behaviour, discrimination, and hate. We must create cultures where each of us can speak out without fear of reprisal when confronted with ethically challenging situations.

Two weeks after I delivered the Holocaust education lecture, our daughter was born. We named her after my grandmother, who survived the Holocaust because she was strong, but who thrived afterwards because despite the incredible hardships she faced in her life, she maintained a profound kindness and generosity towards everyone, and always sought to understand and care for others. Despite the challenging times that face us, I know that by remembering the lessons of the past, we can forge a brighter future.

Dr. Ariel Lefkowitz (PGME ’18, M.Ed ’20), is an internal medicine specialist practicing as a clinical associate at Sunnybrook Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital, as well as a lecturer in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Medicine.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Anatomy of a Discovery: Exploring the Impact of New Salivary Gland Finding

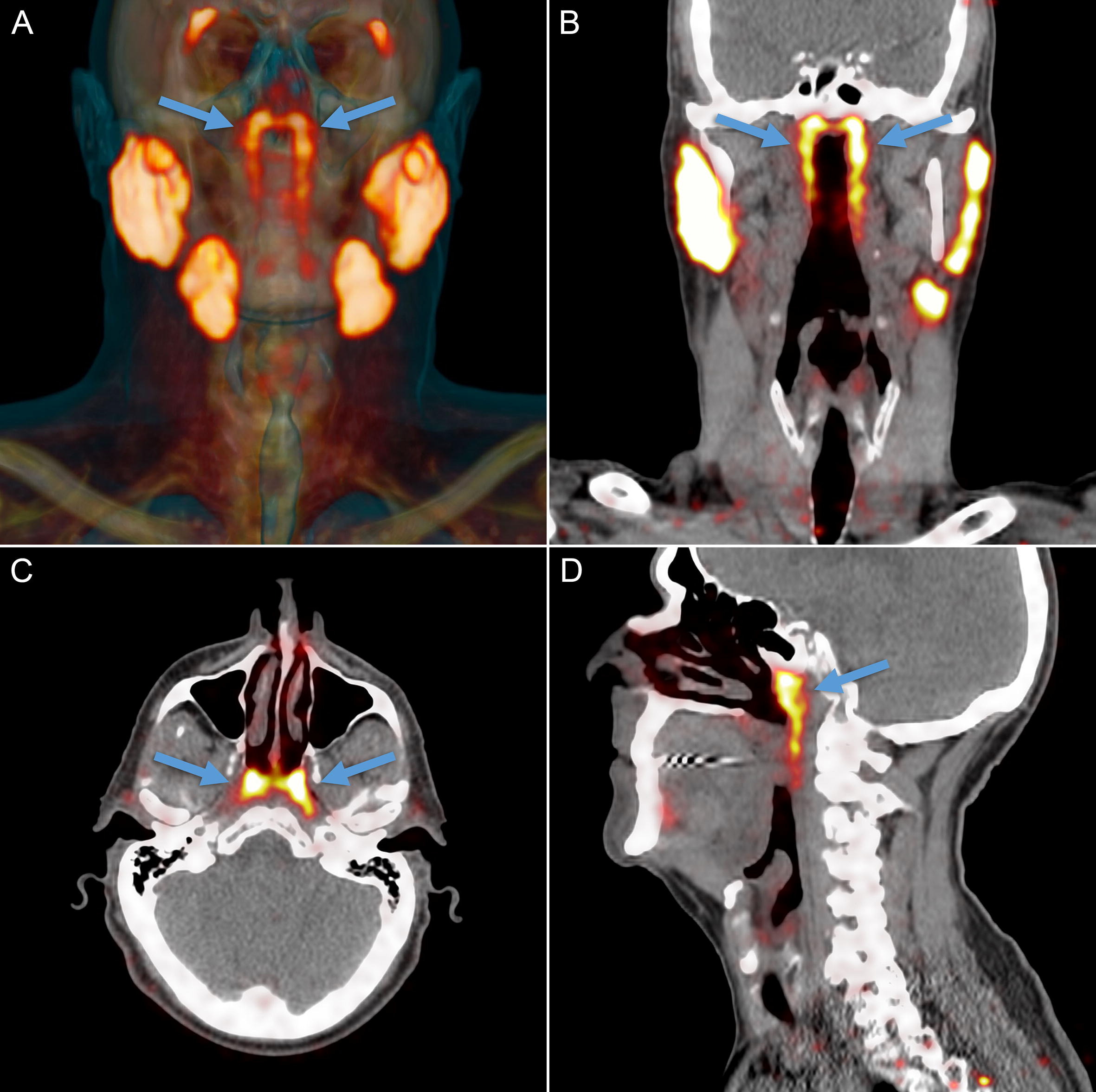

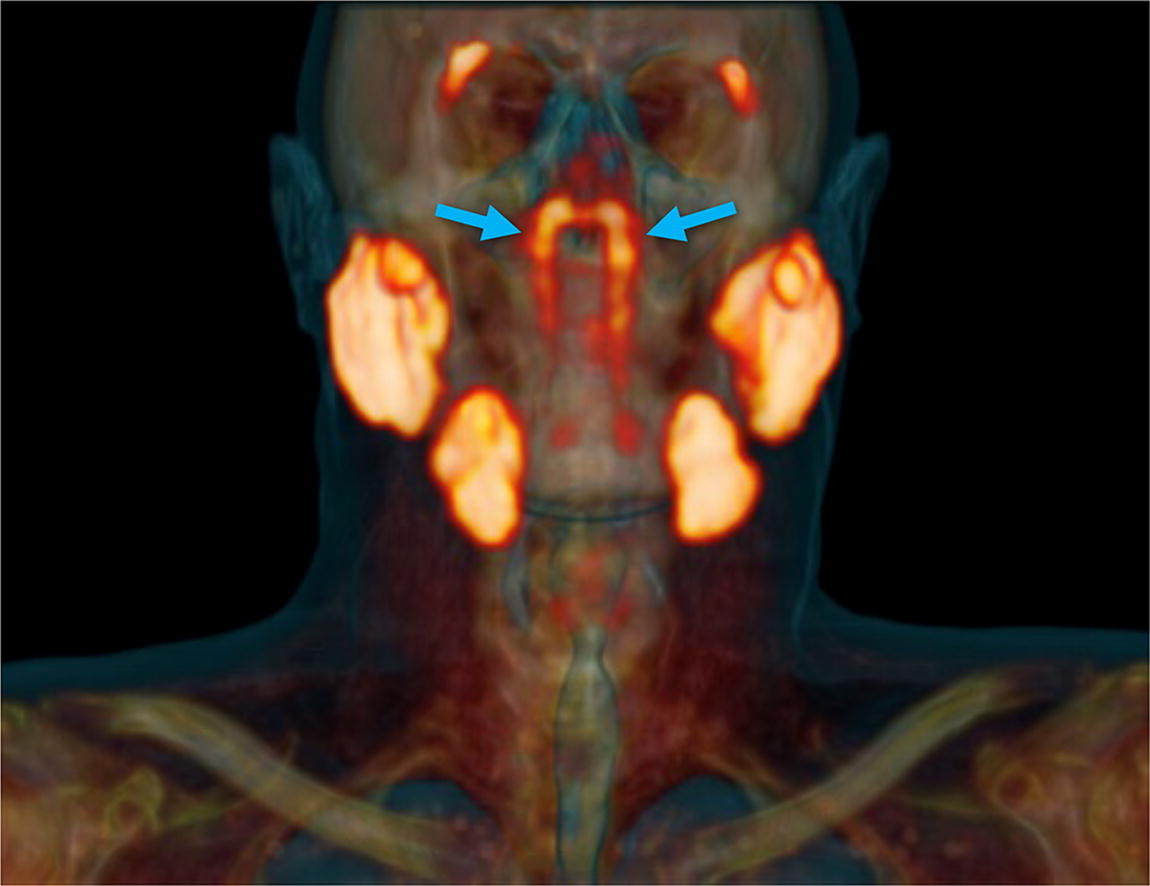

It’s not every day a new part of the human body is identified. But, that’s what happened when scientists at the Netherlands Cancer Institute found a pair of previously overlooked salivary glands behind the nose. The researchers have dubbed them tubarial glands and believe they may be used to moisten and lubricate the upper part of the throat and back of the nose. Allan Vescan, a professor and Director of Undergraduate Medical Education in the Department of Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery whose primary clinical appointment is at Mount Sinai Health System, spoke with Temerty Medicine writer Erin Howe about the finding.

How exciting is it, that in the year 2020, a new organ is discovered?

It's very rare to find something like this. We assume most of the discoveries in human anatomy occurred centuries ago and all we're left to do is make the names easier to remember and teach. It's not often that we encounter something entirely new like this salivary gland. I was quite shocked to read about it.

Because the discovery of these tubarial glands is so recent, what might need to happen to replicate the findings and have them become accepted as established knowledge?

These salivary glands were found during imaging investigations for prostate cancer. To confirm these types of findings, additional anatomical studies will be needed. Something like this could be done in as little as a year or two.

The new salivary glands were found using a type of imaging used to look at the prostate. But they weren’t visible using more traditional imaging methods to look at this part of the body — CT, MRI or ultrasound. Can you tell me more about this?

Those imaging modalities are so detailed and that’s why it's such a remarkable, almost unbelievable, discovery. We always knew there was salivary tissue in the back of the nose, but the study shows this is an organized major salivary gland, which is what’s unique.

The tissue lines this area of the body in a way that isn't obvious to conventional imaging. Only by looking at functional imaging, can we see this tissue is organized in a way that makes it a major salivary gland and not just a bunch of small, scattered minor salivary glands.

The study’s authors highlight the potential to spare these glands during radiation therapy, which could improve the quality of life for people undergoing cancer treatment. What other implications might there be?

I think it's going to help further our understanding of functional issues with saliva and mucus production in the back of the nose. It may also allow us to target therapy to these areas during surgical or medical treatments.

One of the most troublesome quality-of-life side effects for patients who’ve been through radiation to the head and neck is losing the function of their major salivary glands. They end up with problems related to saliva production — dry mouth, dry throat, difficulty swallowing and eating or difficulty with their speech. Salivary cancer is very rare, but these findings might also help us understand some of its nuances, the origins of these tumors and how to best treat them.

One of the most common complaints and concerns patients share with their otolaryngologists has to do with post nasal drip. A lot of people experience it, but beyond ruling out things like an infection or sinus issues, we often can’t identify the cause. So, perhaps this finding could help us better understand this problem.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Supporting New Generations of Diabetes Researchers: The Eli Lilly Clinician-Scientist Trainee Fellowships in Diabetes

For nearly a century, stretching back to the discovery of insulin in 1921, the University of Toronto has been a world leader in diabetes research. It’s an extraordinary legacy of discovery that has been further strengthened in recent years thanks to the generosity of Eli Lilly Canada.

In 2018, the company made a philanthropic commitment of $480,000 to establish the Eli Lilly Clinician-Scientist Trainee Fellowships in Diabetes. In total, eight one-year fellowships will be supported over four years, with the final two fellowships selected and announced in 2021.

“We’re thrilled to support promising young diabetes researchers through these fellowships,” says Dr. Joanne Lorraine, Medical Director Lilly Diabetes, Eli Lilly Canada. “We see this gift as a wonderful way to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin and honour our company’s history as an early partner of the university, as well as to invest in the next generation of bright and innovative minds.”

“We’re extremely grateful to Eli Lilly Canada for their support,” says Professor Trevor Young, Dean of the Temerty Faculty of Medicine. “Funding for early-career researchers like these helps us advance knowledge and drive innovation. The Eli Lilly Clinician-Scientist Trainee Fellowships in Diabetes are contributing to Toronto’s standing as a global centre of excellence for diabetes research.”

Investigating a gout drug’s impact on the health of people with diabetes

Clinical epidemiology — the study of how often different health events occur in different demographics and why — has always been something to which Dr. Alanna Weisman has found herself drawn.

Clinical epidemiology — the study of how often different health events occur in different demographics and why — has always been something to which Dr. Alanna Weisman has found herself drawn.

“I love the challenge and enjoy pushing boundaries,” she says. “We need to understand why we, as physicians, do the things we do.”

When awarded one of the 2018-2019 Eli Lilly Clinician-Scientist Trainee Fellowships, Weisman investigated the effect allopurinol, a drug traditionally used to treat gout, has on people with diabetes. Her work was focused on assessing the drug’s impact on their likelihood of developing cardiovascular and kidney disease.

“There’s been growing interest that allopurinol might actually be beneficial for people with diabetes,” says Weisman. “My colleagues and I collected health data from all over Ontario and looked at the impact over several years. While the drug doesn’t appear to have much of an effect on kidney disease, we were able to find a lowered risk of cardiovascular disease, which causes heart attacks and strokes. Now this is the focus of clinical trials that may help people with diabetes lower their risk of developing these diseases in the future.”

Weisman believes U of T was the ideal place to pursue her work.

“The University is world-renowned for its quality of medical education and research,” she says. “There aren’t many programs that support clinician-scientists in Canada. There’s also such depth of expertise on diabetes here. It’s a nice feeling to know that my work is tied to the legacy of Banting and Best.”

Building better transplant options for people living with diabetes

Dr. Paraish Misra describes the current treatments available to patients with type 1 diabetes for the management of their disease with one word: limited.

Dr. Paraish Misra describes the current treatments available to patients with type 1 diabetes for the management of their disease with one word: limited.

“There reality is there aren’t many options for people living with type 1 diabetes,” says Misra. “The most common way is by administering insulin — a process that can be very disruptive to patients’ lives. The other, is through pancreas or islet transplantion which, when it works properly, is extremely effective. The problem is few donated organs are available for transplant and, even when they are donated, there’s a high risk of rejection.”

Misra, who received the Eli Lilly Clinician-Scientist Trainee Fellowship in Diabetes in both 2018-2019 and 2019-2020, believes the solution to both these challenges lies in lab-grown organs.

“Lab-grown organs remove the limitations around supply,” he says. “And we’re currently growing our islets from (genetically) engineered stem cells which should have a much lower risk of rejection.”

Misra is optimistic his early work using animal and test tube models will confirm his hypothesis and that it could be the launching point for a major advance in the treatment of type 1 diabetes.

He also points to the value his role as clinician-scientist in contributing to his research approach.

“My lab may be focused on what we call ‘basic science,’ but there’s been a lot of synergy with my patient work. I’m always reminded of our goal to see our research applied in clinical settings.”

Assessing the accuracy of tools used to gauge the risk of cardiovascular disease in people with diabetes

Dr. Maneesh Sud believes in questioning everything — including how physicians currently assess patients living with diabetes’ risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Maneesh Sud believes in questioning everything — including how physicians currently assess patients living with diabetes’ risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

“We use tools — basically equations — to calculate how likely someone is to develop heart attacks or strokes,” says Sud. “The problem is these tools were developed many decades ago based exclusively using American data. My project is to determine how these equations work and how well they can be applied to Canadian patients with diabetes.”

Sud, a 2019-20 recipient of the Eli Lilly Clinician-Scientist Trainee Fellowship in Diabetes, believes his research could result in improving how we advise Canadians living with diabetes about their future heart disease risk.

“These drugs can have side effects,” says Sud. “It’s no longer clear the patients we’re currently prescribing drugs for actually need to take them. Maybe some patients can be treated effectively through lifestyle changes and start these medications a few years down the road.”

Sud credits his clinical work as a cardiologist as the inspiration for his research.

“I routinely see patients presenting with heart disease,” he says. “I was drawn to this field by the recognition that there are lots of patients with risk factors for heart disease, but that no modern prediction tools exist specifically for the Canadian setting. With big data, it looks like something we can do now. It’s a unique opportunity at a unique time.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

U of T Researchers Identify an Eye Signature for ALS

In a recently-published article in the journal Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, U of T researchers share their discovery that individuals with ALS show tell-tale changes in the layers of their retinas — the membrane that lines the inner surface of the back of the eyeball.

“ALS is challenging to diagnose, and can often present differently from patient to patient,” says Dr. Yeni Yucel, Professor in the University of Toronto’s Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences and a pathologist-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital and Keenan Research Center for Biomedical Science. “Now, with this new knowledge, we may be able to rapidly speed up diagnosis using equipment that is already found in most ophthalmology clinics.”

The team examined the retinas from 10 deceased ALS patients. Early on, it became clear that there was something different going on in the innermost retinal layers of these patients. Retinal spheroids — unusual round bodies resembling lesions found in the spinal cord of people with ALS — were spotted. Painstaking care was taken to count and examine these retinal spheroids. Their significance in ALS was confirmed when compared to normal retinal tissue, as published today.

“This finding is especially important because it points to a new biomarker for ALS in the eye that we hope will help to diagnose and monitor disease progression non-invasively with retinal imaging tools.” says Yucel.

“My research has been focused on blinding eye diseases,” says Yucel. “After losing dear friends to this devastating disease I wondered if maybe the eye could help us understand the disease better.”

He also is quick to point out the unique impact of U of T’s working environment in contributing to his work.

“U of T, with its affiliated hospitals, is a great ecosystem for research like this,” says Yucel. “There’s a real atmosphere of collaboration. Bright students, Kieran Sharma and Maryam Amin Mohammed Amin, worked on this together with Dr. Neeru Gupta, an ophthalmologist at St. Michael’s Hospital and Professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences, as well as with Dr. Lorne Zinman, a neurologist at Sunnybrook Hospital and Associate Professor with the Department Medicine. We were also fortunate to have support from the Henry S. Farrugia Ophthalmic Research Fund and the Dan Sullivan Research Fund for our work.”

Looking ahead, Yucel is excited to begin exploring the clinical applications of the team’s research.

"Now that we have the eye as our target, we are looking to bring this discovery to ALS patients. Using the patients' eyes as a window to this disease, ultimately we want to use it to deliver better care for people with ALS," says Yucel.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

U of T Researchers Receive $1.5 million in CFI Funding to Launch Unified COVID-19 Biobank

U of T researchers have been awarded $1.5 million by the Canada Foundation for Innovation’s (CFI) Exceptional Opportunities Fund to establish the UT COVID-19 Biobank, integrating existing COVID-19 biobanks across Toronto.

The UT COVID-19 Biobank will provide safe, secure and standardized collection of biologic samples, such as blood and respiratory secretions, that are critical to answering a range of research questions about COVID-19 infection across the age span from children to the elderly.

It will support the collection of more than half a million samples of biologic data collected from more than 57,000 Canadians, including patients with COVID-19, family members, health-care professionals and controls. These samples will be collected in 72 U of T-led studies.

The funding was announced by The Honourable Navdeep Bains, Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry, on November 6, and was part of close to $28 million in funding through CFI’s Exceptional Opportunities Fund, created to support urgent needs for equipment for ongoing research related to COVID-19.

“We are grateful to CFI for this important funding. With the launch of the UT COVID-19 Biobank, we hope to advance our understanding of COVID-19 across the age span and severity of COVID-19 disease using common collection procedures,” says Dr. Rae Yeung, the project’s principal investigator and a professor in the Departments of Paediatrics, Immunology, and Medical Science at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine at U of T.

Yeung is also a Senior Scientist and a Staff Physician in Rheumatology at SickKids.

“The unique collaboration provided by the biobank will help ensure that important questions about COVID-19 immunity and long-term complications are answered,” says Dr. Rulan Parekh, the co-principal investigator and a professor in the Departments of Paediatrics and Medicine in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

Parekh is also Associate Chief of Clinical Research, Senior Scientist and a Staff Physician in Nephrology at SickKids.

One of the greatest obstacles to inter-institutional and international collaboration is a lack of uniform data collection, and an integrated and centralized biobank is a way to ensure across-the-board consistency. This is particularly important during the current pandemic.

“Many biomarkers associated with COVID-19, such as inflammatory markers, are very unstable in the blood, meaning that if you don’t process them very quickly, they degrade and the measurements do not reflect what’s really going on,” says Yeung.

There are other factors that must be consistent among samples to ensure researchers are “comparing apples to apples,” such as the way samples are processed, how they are stored and transported, and at what temperature.

Some samples must be stored at -80 C to remain stable, requiring highly specialized storage and transportation equipment.

To address these uniformity challenges and increase efficiency, the biobank will create standard operating procedures for all users, including centralized consent and research-ethics frameworks.

The biobank will allow multiple research teams to maximize the use of a single specimen in different studies. This has the added benefit of enhancing infection prevention and control during the pandemic by limiting the number of in-person appointments for study participants, notes Parekh.

Another innovative aspect of the project is that, in order to reach under-serviced and underrepresented populations (many of whom might not otherwise be able to go to downtown hospitals to participate), the project will send a mobile sample-collection unit right into communities across the Greater Toronto Area. The staffed van will meet study participants to provide blood tests and obtain samples that will be added to the biobank.

The project’s other co-principal investigators are Drs. Angela Cheung and Shahid Husain from Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, University Health Network (UHN), and Claudia dos Santos of the Keenan Research Centre at St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto.

“We are incredibly excited about this project,” says Yeung, adding that it came together extraordinarily quickly and enthusiastically. “Everyone wants to help with the COVID situation and has been so generous with their time and expertise.”

“University of Toronto researchers are playing a critical role in addressing the ongoing public health crisis and are working tirelessly to assist the Canadian and global response to the pandemic,” said Christine Allen, U of T’s associate vice-president and vice-provost, strategic initiatives, and a professor in the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy.

“This funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation supports two important research projects that will see experts from U of T and partner hospitals combine their expertise to increase our understanding of COVID-19 and improve the lives of Canadians affected by this deadly disease.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

A Coach’s Gift: $1-million Estate Donation to Support Parkinson’s Research

The late Robert (Bob) Cunningham of Cambridge, Ontario loved helping others succeed.

The late Robert (Bob) Cunningham of Cambridge, Ontario loved helping others succeed.

“Bob was a coach through and through,” says his godson, Stephen Reynolds. “He was a mentor to me, and to many others in business, sports and beyond.”

While Cunningham passed away following a short illness in June 2020, his generous spirit will live on in perpetuity following his estate’s $1-million gift to the University of Toronto’s Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

Unusual for most planned gifts, the decision to support the Tanz Centre wasn’t made by Cunningham himself. Instead, he left the choice of which organizations to support to his estate’s trustees.

“Bob had a lot of conversations with us before he passed, but didn’t give us much in terms of specific directions,” says Reynolds, who serves as a trustee alongside his father, William Reynolds, and Cunningham’s cousin, Douglas Bowman. “All he cared about was having an impact. Bob wanted us to make sure that whoever benefitted from the estate would earn it or use it to its maximum benefit. He was confident we would come to the right conclusion.”

After learning about the Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Tanz Centre from an advisor, the trustees came to see its researchers’ work as aligning with Bob’s own optimistic approach to life and natural curiosity.

“Bob was very inquisitive and was always asking questions,” says Reynolds. “He was also extremely positive. A problem was never insurmountable — it just had to be taken on. He challenged pessimism. Important research doesn’t always get funded. Blue sky stuff needs to be sponsored too. He’d be happy with this prudent risk — it’s an investment in hope.”

Delivering hope is exactly what the new Robert L. Cunningham Parkinson’s Research Award seeks to do. Each year, the endowed fund will provide a scientist with a prestigious award in support of research into Parkinson’s Disease — a progressive nervous system disorder affecting nearly 1 out of every 500 Canadians for which there is currently no cure.

“This new award will help expand our understanding of Parkinson’s disease and support vital research that could lead to potential new treatments,” says Professor Graham Collingridge CBE, FRS, director of the Tanz Centre. “As an endowed award, its impact will be felt forever. My colleagues and I are very grateful.”

Reynolds points out this gift is just the latest in a long line of Cunningham’s philanthropic contributions.

“He believed that in life you have to give back to your community,” says Reynolds. “Bob spent more than 30 years coaching minor league hockey and baseball in Cambridge. Several years ago, he established scholarships for local high school student-athletes. He also served on the board of both the Cambridge Memorial Hospital and its foundation. The Intensive Care Unit there is named in his honour.”

As someone who received decades of advice and mentorship from his beloved godfather, Reynolds believes the way Cunningham arranged his estate was meant to provide an important final lesson.

“I think Bob left this money as a challenge to see what we would do,” says Reynolds. “He wanted us to understand the value of what giving meant. He was hoping we would take on that mantle and carry his legacy forward, to make us better people. In all sincerity, the opportunity to give away his legacy has been a gift to us all. He was a very special man.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

Partnering on Better Outcomes for Veteran Mental Health

La version française suit

Championing veterans’ greater access to quality mental health care is the mission-of-a-lifetime for Ryan Dermody, President of Norcan Petroleum Group and retired member of the Royal Navy.

Championing veterans’ greater access to quality mental health care is the mission-of-a-lifetime for Ryan Dermody, President of Norcan Petroleum Group and retired member of the Royal Navy.

“I’ve seen, firsthand, what happens when veterans living with mental health conditions fail to get the help they need,” says Dermody. “Governments and other organizations have been doing important work in this area. Yet, there are still many times when individuals slip through the cracks, often with tragic outcomes. We have to do better.”

Dermody, who also serves as a member of the University of Toronto’s Department of Psychiatry Volunteer Campaign Cabinet, began asking what the department was doing to help address this challenge.

“Ryan’s question was an eye-opener,” says Professor Benoit Mulsant, Labatt Family Chair of the Department of Psychiatry in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine. “We pride ourselves on our department’s size and broad scope, and yet, we realized we were not doing enough in the specific area of veteran mental health.”

Recognizing this, the Department commissioned a study in 2018 to explore how to augment current treatments and supports for Canadian veterans with a focus on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“We don’t want to duplicate existing programs,” says Mulsant. “The study was commissioned to determine if there was a role we can play, given our expertise in care, education, and research, to add to these efforts in a strategic way.”

The final, 76-page report identified several key gaps in the current state of veterans’ psychiatric care. The most glaring: that most clinicians practicing in Canada are unfamiliar with military culture and lack experience treating trauma-related conditions in veterans.

“As a university that trains more than a quarter of the country’s psychiatrists we feel a particular responsibility to help address this issue,” says Mulsant. “One way would be through new fellowships in veteran mental health that would provide new psychiatry leaders with targeted training in this highly-specialized field.”

The study also identified a need to advance research into conditions for which veterans are at particularly high risk (such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use), as well as for further collaboration between the many stakeholders already working to support veteran mental health — opportunities Mulsant sees aligning with U of T’s strengths and expertise.

“We are embarking on this journey without yet knowing all the answers, but my colleagues and I are confident that we can contribute in a positive way to the wellbeing of Canadian veterans,” says Mulsant. “Our next step will be consulting with veterans, and veterans’ organizations, to co-create solutions that will leverage our strengths. We plan to create an advisory committee that will guide us and ensure that our programming is veteran-centric and integrative.”

“We always welcome initiatives across the country that seek to improve mental health outcomes for our Veterans,” says The Honourable Lawrence MacAulay, Minister of Veterans Affairs and Associate Minister of National Defence. “Academic institutions like the University of Toronto are important collaborators in driving health innovation.”

Early lead donors, including National Bank and Fondation Famille Vachon, have already stepped forward in support of the department’s efforts. A portion of their support will fund a pilot training opportunity for junior psychiatrists from Quebec and the rest of Canada to train at U of T.

“We’re thrilled to be supporting U of T’s Department of Psychiatry’s work in the area of veteran mental health,” says Louis Vachon, President and Chief Executive Officer of National Bank and Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal. “Members of the military serve their communities with selfless courage, skill and unwavering dedication. We owe it to our veterans to do all we can to ensure their wellbeing.”

For more information on the Department of Psychiatry’s efforts to improve veterans’ mental health care, or to make a gift to the initiative, please contact Gabrielle Dang at gabrielle.dang@utoronto.ca.

Partenariat pour de meilleurs résultats pour la santé mentale des vétérans

Promouvoir un meilleur accès aux anciens combattants à des soins de santé mentale de qualité est la mission de toute une vie pour Ryan Dermody, président de Norcan Petroleum Group et membre retraité de la Royal Navy.

« J’ai vu de mes propres yeux ce qui se passe lorsque des vétérans souffrant de problèmes de santé mentale ne parviennent pas à obtenir l’aide dont ils ont besoin », a déclaré Ryan Dermody. « Les gouvernements et d’autres organisations ont accompli un travail important dans ce domaine. Pourtant, il y a encore de nombreuses occasions où des individus passent entre les mailles du filet, souvent avec des conséquences tragiques. Nous devons faire mieux. » a-t-il conclu.

Ryan Dermody, qui est également membre du cabinet de campagne des bénévoles du Département de psychiatrie de l’Université de Toronto, a commencé à questionner sur ce que le département faisait pour relever ce défi.

« La question de Ryan a été révélatrice », a déclaré le professeur Benoit Mulsant, directeur de la Labatt Family Chair du département de psychiatrie de la faculté de médecine de Temerty. « Nous sommes fiers de la taille et de la portée de notre service, mais pourtant, nous avons réalisé que nous n’en faisions pas encore assez dans le domaine spécifique de la santé mentale des anciens combattants. »

Conscient de cette situation, le Ministère a commandé une étude en 2018 pour explorer comment augmenter les traitements et le soutien actuel pour les anciens combattants canadiens en mettant l'accent sur le trouble de stress post-traumatique (TSPT).

« Nous ne voulons pas dupliquer les programmes existants », a commenté Benoit Mulsant. « L'étude a été commandée pour déterminer s'il y avait un rôle que nous pourrions jouer, compte tenu de notre expertise en matière de soins, d'éducation et de recherche, pour compléter ces efforts de manière stratégique » de poursuivre Benoit Mulsant.

Le rapport final de 76 pages a identifié plusieurs lacunes importantes dans l’état actuel des soins psychiatriques pour les anciens combattants. Le plus flagrant : la plupart des cliniciens qui exercent au Canada ne connaissent pas la culture militaire et manquent d'expérience dans le traitement des conditions liées aux traumatismes chez les anciens combattants.

« En tant qu’université qui forme plus d’un quart des psychiatres du pays, nous nous sentons particulièrement interpellé pour aider à résoudre ce problème. Une solution serait de créer de nouvelles bourses dans le domaine de la santé mentale pour les vétérans qui fourniraient aux nouveaux leaders en psychiatrie une formation ciblée dans ce domaine hautement spécialisé. » a déclaré Mulsant.

L'étude a également identifié le besoin de faire progresser la recherche sur les conditions pour lesquelles les vétérans sont particulièrement à haut risque (comme le SSPT, la dépression, l'anxiété, la consommation de substances), ainsi que pour une collaboration plus poussée entre les nombreux intervenants qui travaillent déjà à soutenir la santé mentale des vétérans. Une opportunité que Mulsant voit s'aligner sur les forces et l'expertise de l'Université de Toronto.

« Nous entreprenons cette belle aventure sans encore connaître toutes les réponses, mais mes collègues et moi sommes convaincus que nous pouvons contribuer de manière positive au bien-être des anciens combattants canadiens », a jouté Mulsant. « Notre prochaine étape consistera à consulter les anciens combattants et les organisations d’anciens combattants, afin de co-créer des solutions qui tireront parti de nos forces. Nous prévoyons créer un comité consultatif qui nous guidera et veillera à ce que nos programmes soient centrés sur les vétérans et les intégrateurs.

«Nous accueillons toujours les initiatives partout au pays qui visent à améliorer les résultats en santé mentale de nos anciens combattants», a déclaré l'honorable Lawrence MacAulay, ministre des Anciens Combattants et ministre associé de la Défense nationale. «Les établissements universitaires comme l'Université de Toronto sont des collaborateurs importants dans la promotion de l'innovation en santé.

Les premiers donateurs principaux, dont la Banque Nationale du Canada et la Fondation Famille Vachon, se sont déjà engagés à soutenir les efforts du ministère. Une partie de leur soutien financera un projet pilote de formation pour les psychiatres en formation du Québec et du reste du Canada afin qu'ils se forment à l'Université de Toronto.

Nous sommes ravis d’appuyer le travail du Département de psychiatrie de l’Université de Toronto dans le domaine de la santé mentale des vétérans », a déclaré Louis Vachon, président et chef de la direction de la Banque Nationale du Canada et lieutenant-colonel honoraire des Fusiliers Mont-Royal. Les militaires servent leurs communautés avec un courage inébranlable, des compétences et un dévouement sans faille. Nous devons à nos anciens combattants de faire tout ce que nous pouvons pour assurer leur bien-être » de conclure Louis Vachon.

Pour plus d’informations sur les efforts du Département de psychiatrie pour améliorer les soins de santé mentale des anciens combattants ou pour faire un don à l’initiative, veuillez contacter Gabrielle Dang à gabrielle.dang@utoronto.ca.

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

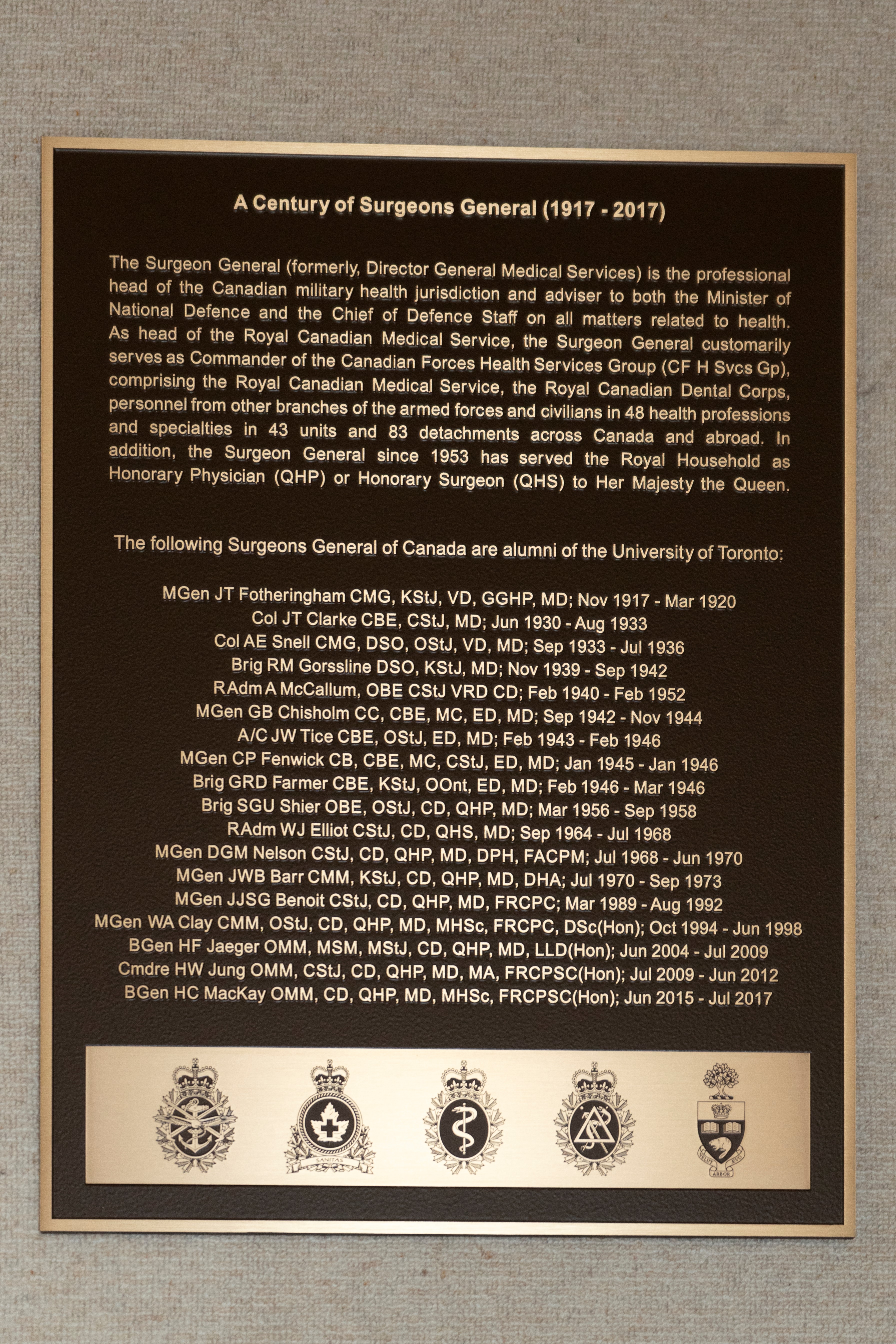

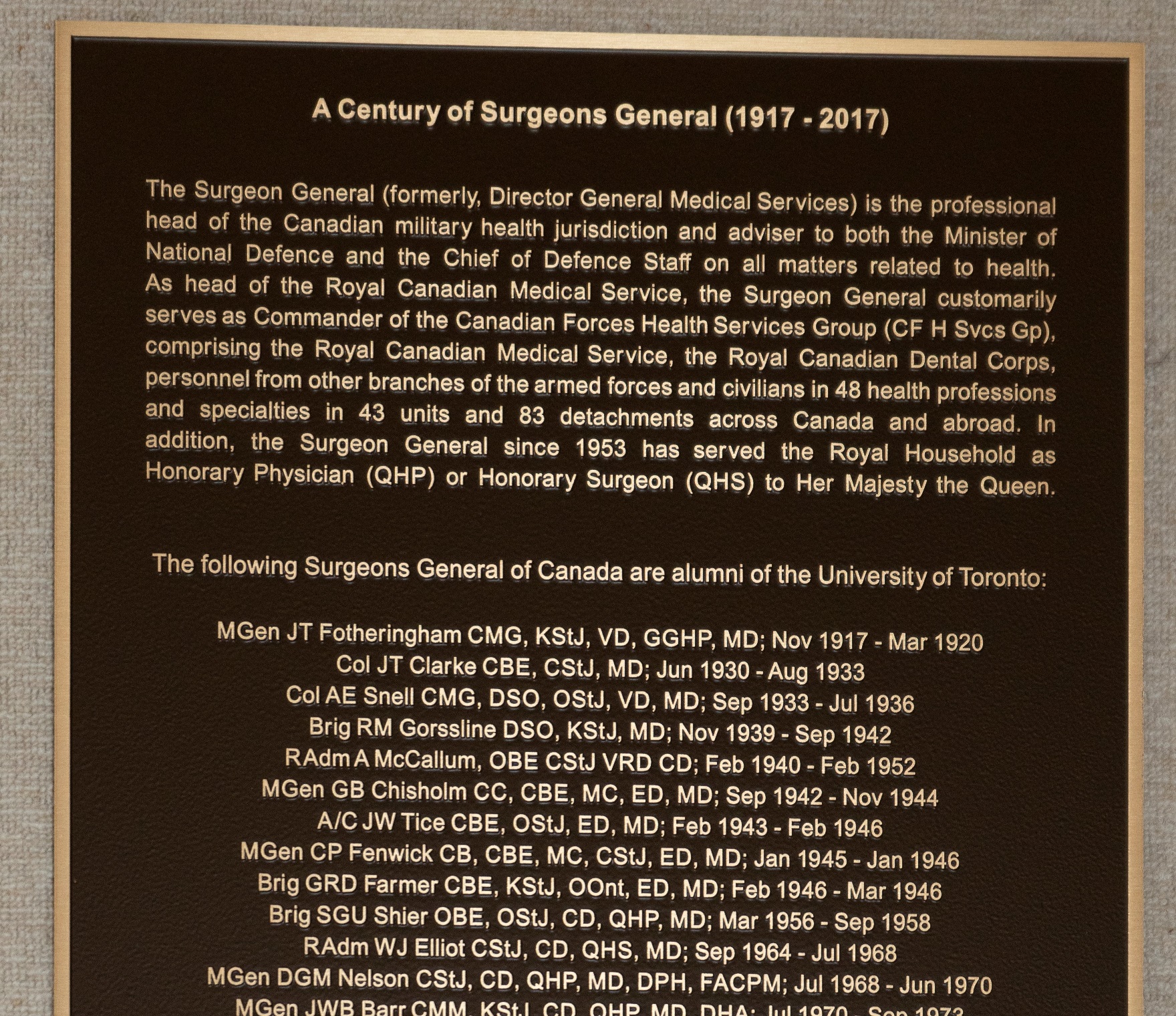

U of T to Honour Long Legacy of Military Medical Leadership

A new plaque in the Medical Sciences Building will honour the University of Toronto’s track record of leadership in Canadian military medicine.

Since 1885, 47 individuals have served the Canadian military as Surgeon General (or Director General of Medical Services, as the role was previously known). Nearly half of the holders of this prestigious position have been University of Toronto alumni.

“The Surgeon General is the professional head of the Canadian military who oversees all matters related to health,” says Professor Trevor Young, Dean of the Temerty Faculty of Medicine. “The fact that so many U of T alumni have served in this important role speaks both to the quality of our graduates, as well as to our alumni’s strong tradition of military service.”

As head of the Royal Canadian Medical Service, the Surgeon General also has traditionally served as Commander of the Canadian Forces Health Services Group. The Health Services Group is made up of the Royal Canadian Medical Service, the Royal Canadian Dental Corps, as well as personnel from other branches of the armed forces and civilians in 48 health professions and specialities in 43 units and 83 detachments across Canada and abroad. In addition, the Surgeon General also has traditionally served the Royal Household as Honorary Physician or Honorary Surgeon to Her Majesty the Queen.

The new plaque, honouring a century of U of T-affiliated Surgeons General stretching from 1917 to 2017, will be unveiled in a special ceremony following the end of restrictions on in-person gatherings due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Its creation was made possible thanks to the leadership of alumnus Dr. Michael Dan (MD ‘84).

“I’m thrilled to be able to help U of T honour its many alumni who have served Canada and Canadians and continue to serve in leadership roles within the Canadian Armed Forces,” says Dan. “The Surgeon General is an extremely prestigious medical appointment that carries with it tremendous responsibilities. The number of U of T alumni who have gone on to serve as Surgeons General in Canada is a truly remarkable legacy and relationship with medical leadership that no other Canadian university can match.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.

Emily Kulin

‘Our very first biotech win’: How U of T’s discovery of insulin made it a research and innovation powerhouse

For nearly four decades, Patricia Brubaker has been investigating the biological activities of anti-diabetic gut hormones secreted by the intestine.

Her work is focused on the fundamental biology of the hormones and has contributed to development of drugs for the treatment of patients with Type 2 diabetes. The drugs work by stimulating the secretion of insulin, helping to lower blood sugar levels and reducing appetite, among other effects.

Brubaker understands all too well the impact such research has had on people’s lives – she is a Type 1 diabetes patient herself.

“The progress over the last 40 years has been simply phenomenal in terms of how people with diabetes are treated clinically, the extension of their life spans and the prevention of complications,” says Brubaker, a professor in the departments of physiology and medicine in the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine and a member of the faculty’s Banting & Best Diabetes Centre.

Brubaker, a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada who recently won a lifetime achievement award from Diabetes Canada, says huge strides are being made in the treatment of the disease, which affects as many as one out of three Canadians when the condition known as prediabetes is taken into account.

But she stresses that research on prevention is equally crucial.

“What we need to do is figure out how we can prevent diabetes in the first place,” she says.

“Diabetes prevention science is going to be all about how we can predict the onset of diabetes, which is great. But if we know someone’s going to develop diabetes, how do we prevent it? That’s still an area of intense investigation.”

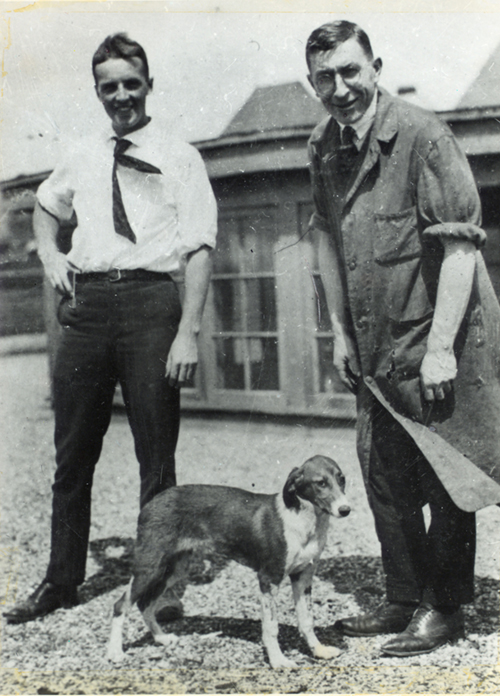

These and other pressing questions on the future of diabetes treatment and prevention science will be addressed by Brubaker and other experts at a Nov. 26 panel discussion that’s part of a virtual symposium examining the impact of the discovery of insulin by U of T’s Frederick Banting and Charles Best, who worked with J.J.R Macleod and James Collip. “The Legacy of Insulin Discovery: Origins, Access, and Translation” will examine insulin and diabetes from a range of perspectives, including laboratory research, clinical practice, pharmacy, commercialization, entrepreneurship, digital technology and socio-economic factors.

It’s the first in a series of events organized by U of T to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, and one of the highlights of the 2020 Celebration of Excellence and Engagement, a week-long exploration of scholarly, scientific and artistic topics presented by U of T and the Royal Society of Canada.

Learn more about the Nov. 26 insulin symposium

“The discovery of insulin by Frederick Banting and Charles Best, and their team, is a testament to what we can achieve when we empower scientific research and find ways to share it with the world,” says University Professor Ted Sargent, U of T’s vice-president, research and innovation, and strategic initiatives.

“The discovery of insulin by Frederick Banting and Charles Best, and their team, is a testament to what we can achieve when we empower scientific research and find ways to share it with the world,” says University Professor Ted Sargent, U of T’s vice-president, research and innovation, and strategic initiatives.

“That extraordinary work done in the early 1920s not only saved millions of lives, it laid the foundation for the University of Toronto’s world-class student training programs and robust partnerships with hospitals and industry – collaborations that continue to revolutionize health care today.”

Brubaker says collaborations have been crucial in her research career. Recently, she’s partnered with researchers who study gut bacteria, which appears to play a role in the production of the gut hormones that she studies: GLP-1 and GLP-2.

Read more about U of T researchers whose gut hormone work advanced diabetes care.

She says our improved understanding of GLP-1 has led to the development of drugs that can mimic the actions of the hormone, which is naturally secreted by the intestine and helps produce more insulin to keep blood sugar levels in check. It has also led to the advent of DPP-4 inhibitors, a class of prescription medicines that slow the inactivation and degradation of GLP-1, making it last longer in the body.

“The long-term goal is that, if we can promote higher release of GLP-1 into the bloodstream and then maybe combine that with the DPP-4 inhibitors, we might end up with a better combination therapy,” Brubaker says.

Her lab has also been exploring ways to take advantage of the relatively recent finding that release of GLP-1 is time-dependent and influenced by the body’s circadian rhythms.

“GLP-1 is actually secreted at higher levels during different times of the day,” she says.

“Our notion is that maybe we can take advantage of these natural rhythms to help promote release of GLP-1 when our body needs it, and not promote release when our body doesn’t need it.”

Brubaker identifies stem cell therapy and the development of smarter forms of insulin that don’t cause patients’ blood glucose to drop to unsafe levels as other promising avenues of diabetes research.

Yet, when it comes to preventing and treating diabetes, novel research is only one piece of the puzzle.

Paul Santerre, a professor in the Faculty of Dentistry and the Institute of Biomedical Engineering, says the extent of progress on diabetes and insulin will partly depend on how well research breakthroughs from scholars like Brubaker can be married with efforts at commercialization and innovation.

He notes that the discovery of insulin and its subsequent development and commercialization transformed the lives of millions of people around the world – and offers lessons that are still applicable today.

“When you contemplate the past 100 years, insulin was probably our very first biotech win that didn’t only do the lab work but also executed on the translational aspect – and did it way before Canada and the investor community knew what they held in their hands,” says Santerre, who is cross-appointed to the department of chemical engineering and applied chemistry and the Temerty Faculty of Medicine via his health research at the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research.

He says that while home-grown Canadian commercialization successes in health care could be measured with one or two wins per decade since the success of insulin’s commercialization, a second wind of research commercialization began to blow through the life sciences in Canada in the early 1990s.

“Since my arrival at U of T in 1993, I’ve seen activity in the life sciences innovation sector grow quadratically. The future looks extremely bright and the growth is completely on the right path and must be sustained.”

Santerre will reflect on this growth and the path forward during a panel discussion on commercialization and innovation at the Nov. 26 symposium.

“If we have an innovation agenda and support it in parallel with the discovery programs at the university, we can teach our students about how to do innovation, scale up a technology and introduce it to world markets in a cost-effective manner that the health-care system can afford,” Santerre says. “We will end up with a generation that truly has the ability to execute on discoveries coming out of our university.”

He adds that the introduction and expansion of campus-linked accelerators at universities like U of T has sparked a shift in thinking on campus.

“It’s very different to the way I was trained in the 1980s, and it’s very refreshing to see the innovation economy – certainly as it pertains to health sciences – start to become mainstream here in Canada,” he says.

As co-founder and director of the Health Innovation Hub (H2i), a startup incubator based in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine, Santerre has a front row seat to what he describes as a “paradigm shift.”

He notes that H2i formed in 2014 with seven companies and generated $40,000 in economic value that year. Today, H2i comprises more than 130 early-stage health technology start-up companies that have generated over $45 million in economic value in the Toronto ecosystem this past year.

Santerre adds that H2i has fostered several startups working in diabetes and related areas. Examples include: Nutarniq, which, in partnership with Inuit communities, is running clinical trials on a unique formulation of Omega-3 oils from seals that could alleviate secondary effects of neuropathic events associated with diabetes; and Arterial Solutions, which is commercializing an early biomarker for early peripheral vascular disease, a primary co-morbidity associated with diabetes.

Santerre himself is chief scientific officer of Interface Biologics and Ripple Therapeutics, both venture-backed Canadian companies. Ripple Therapeutics has developed a novel drug delivery technology that could improve the efficacy and convenience of wearable insulin patches.

“It’s really exciting what we’re seeing,” he says. “The innovation economy in Canada is creating jobs that we had never harnessed before. That is keeping our life sciences-trained experts here in Canada and is in fact attracting senior management talent to the Toronto area and drawing companies from across Canada, the U.S. and Europe to work with our homegrown companies.”

Santerre says the impact of the insulin discovery, 100 years after the original investments, continues to be felt at U of T through the Connaught Awards drawn from the Connaught Fund, which was established when U of T sold the lab that produced insulin and other vaccines and antitoxins.

“I know that for a fact because I was a Connaught Award recipient back in 1994, and that small investment went on to produce some 70 patents, five faculty spin-offs and the creation of the Health Innovation Hub, which is spurring a lot more health start-up activity,” he says.

Santerre says that research, entrepreneurship and funding support from sources like the Connaught Fund as well as the recent historic donation to the Temerty Faculty of Medicine are coalescing perfectly to position U of T and Canada for continued leadership in diabetes research and innovation.

“That’s the future,” he says. “We have plans afoot to scale what we’ve learned from the insulin discovery, the Connaught Labs and the impact that those revenues have had on the research and innovation machine here at U of T – not only for diabetes but many other diseases as well.

“I think Canada is a sleeping giant that has awoken.”

Optimize this page for search engines by customizing the Meta Title and Meta Description fields.

Use the Google Search Result Preview Tool to test different content ideas.

Select a Meta Image to tell a social media platform what image to use when sharing.

If blank, different social platforms like LinkedIn will randomly select an image on the page to appear on shared posts.

Posts with images generally perform better on social media so it is worth selecting an engaging image.