Building a Better Diabetes Predictor

Erin Howe

Every year in Canada as many as 20 per cent of pregnant women develop gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), which in most cases is a temporary form of diabetes. Even though the condition usually goes away following delivery of their babies, women who’ve had this transient form of diabetes are about seven times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes (T2D) in the future.

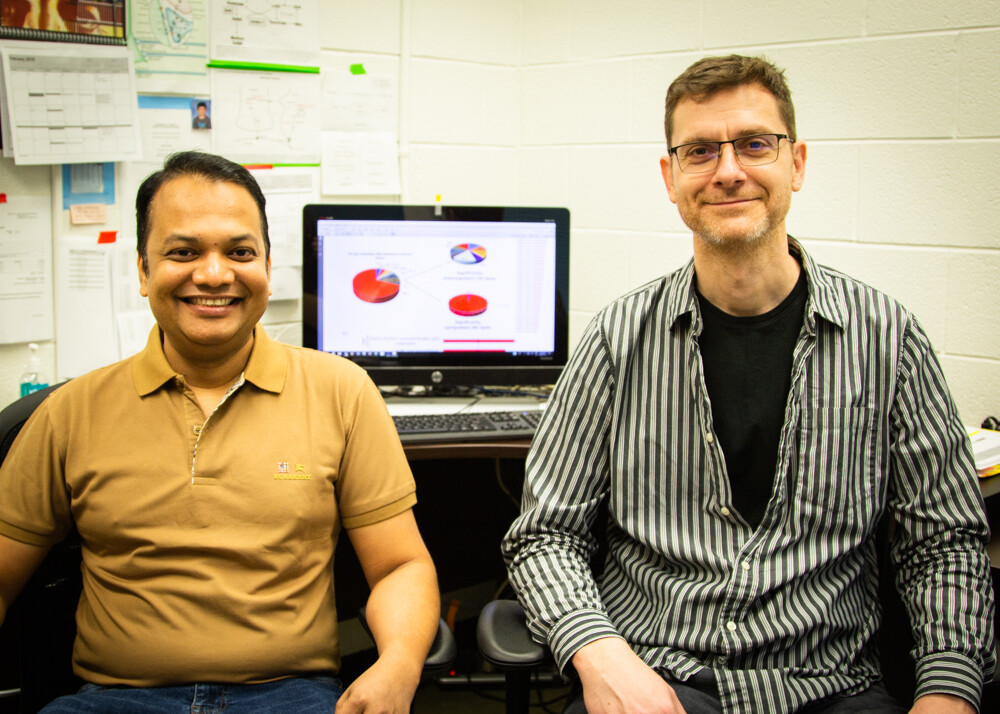

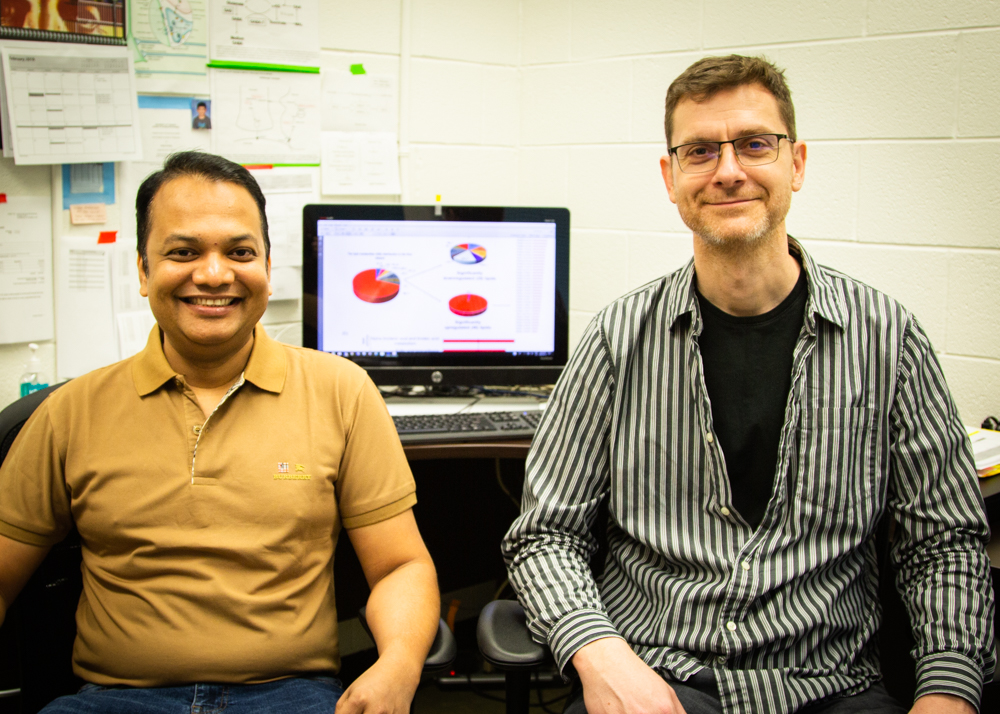

Currently, there aren’t many tools to help predict who will develop the chronic condition, but research by Professors Michael Wheeler and Brian Cox at the Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Physiology could one day change that.

Working with Dr. Erica Gunderson, a senior research scientist at the research division at Kaiser Permanente, a health maintenance organization in Oakland, California, Wheeler and Cox co-led research that’s shed new light on how to determine whether or not women who’ve had GDM will eventually develop T2. The study was recently published in the journal Diabetologia.

The Society of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians of Canada recommend women who’ve had GDM be screened for diabetes between six weeks and six months following delivery, with annual follow ups after that. But, only between 14 and 50 per cent of this group take the initial test and just 20 per cent go back for their annual screen.

“Everybody wants to believe they’ll be in the fifty per cent who won’t develop T2D,” says Cox. “If we could be more confident in predicting who will or won’t get diabetes, that might motivate people to come back for assessment or take on lifestyle interventions to help them reduce their disease risk.”

The study looked at a group of about a thousand women in Southern California who had GDM. After they delivered the babies, scientists followed the women’s health for nearly a decade using oral glucose tolerance tests and a variety of other biochemical and lifestyle tests.

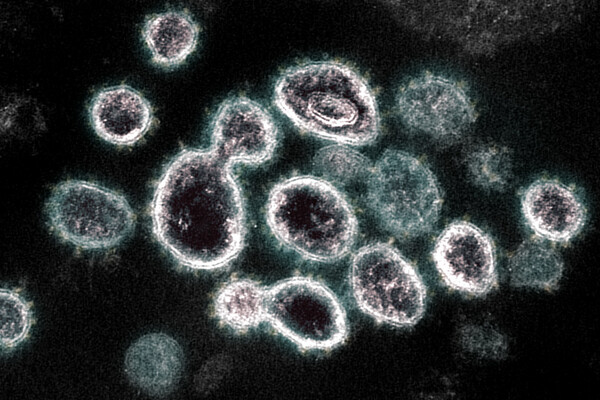

The team identified seven lipids that — depending on their levels — predicted with 92 per cent accuracy whether or not the women would develop T2D. To do it, they used mass spectrometry and artificial intelligence, a technique that can quantify and identify compounds within a sample and help researchers better understand the makeup of different molecules and their association with diabetes risk.

“Everybody focuses on blood sugar. But circulating fats — also known as lipids — are also important in the disease,” says Wheeler, who also has appointments in the Department of Medicine and the Institute of Medical Science. “The relationship could be causal, through obesity or the types of fats people have in their diets. Knowing this, we used lipidomics — which allowed us to look at more than a thousand lipids in a short time from one small blood sample.”

Genetics, regional differences and environmental factors can all influence people’s lipid levels. The hope is to find a simple lipid signature that is common among all woman that can predict diabetes. The seven lipids identified in this study represent a significant step towards this goal with respect to those with GDM who transition to T2D.

The team plans to explore whether their findings are more broadly applicable.

As a next step, Wheeler and Cox hope to develop a test that could be used in a clinical chemistry lab, where many patients already have multiple types of bloodwork done. Cox points out there are already assays to measure other lipids like cholesterol. Now, the pair say it’s a question of developing something similar to test for the seven lipids identified in the study.

The idea, says Wheeler, is to create a simple test to more accurately predict future T2D using a small blood sample taken before women leave the hospital after delivering their babies deliver — or even a few weeks or months later. Since the current tests are only able to make predictions for small windows of time, the team’s goal is to eliminate the need for women to return repeatedly for monitoring.

Wheeler and Cox’s most recent study builds on earlier research published in 2016 in which they identified a series of metabolites that could predict T2D in women who’d experienced GDM.

They’ve patented some of their earlier findings and connected with the University’s Innovations & Partnerships Office in the hopes of one day developing a diagnostic test. But, the pair emphasizes that a clinical application for their findings is still years away.

Wheeler also says there’s potential to use the knowledge to help develop a new screening tool for all people — which could have a massive impact globally.

“It shows the necessity of discovery-based science when it comes to developing things that could be translated into new medical applications,” says Cox. “There’s a lot of pressure on translation, but if we don’t do this basic research, there’s nothing to translate.”

The research was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

News